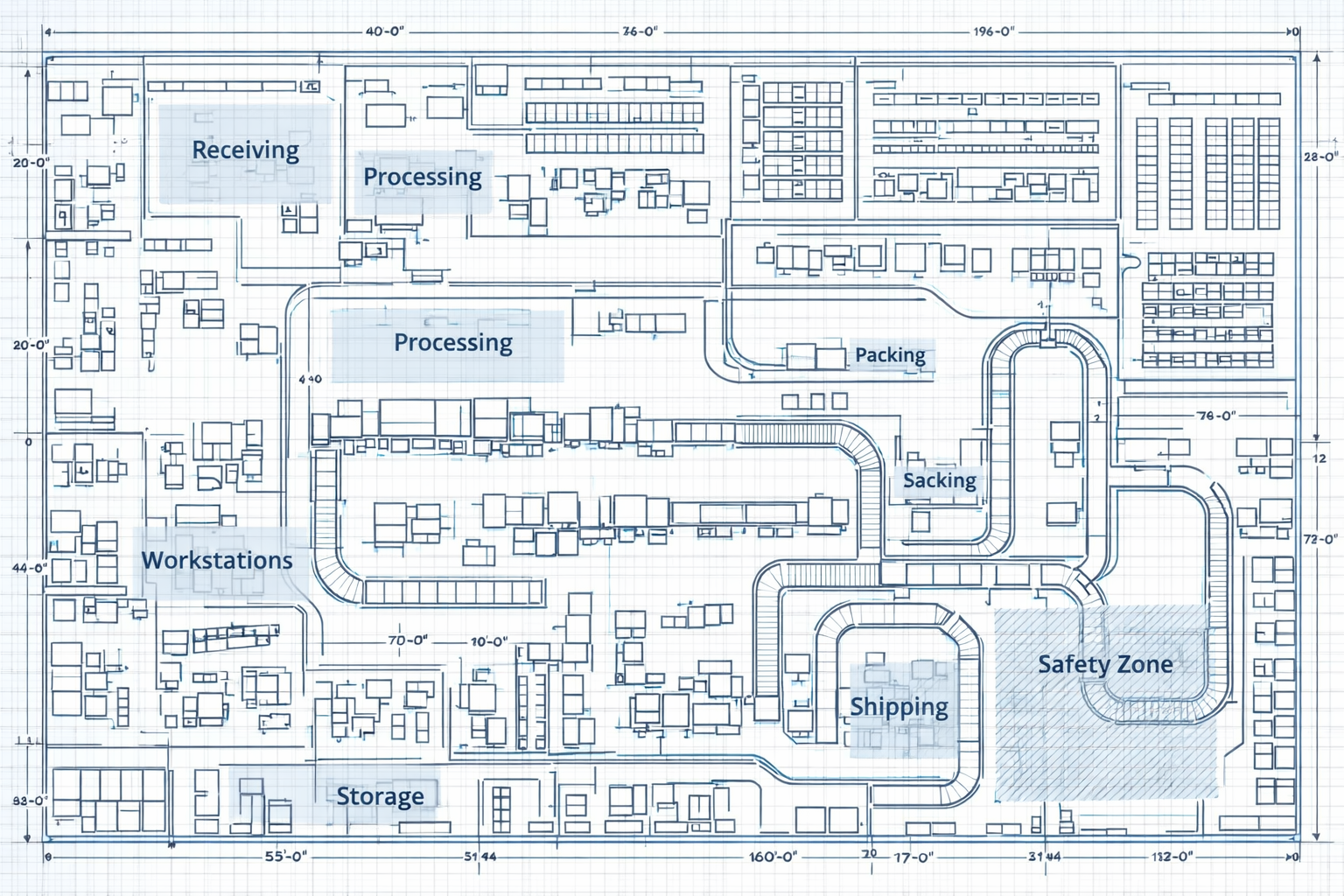

Why “Perfect” Layouts Struggle in Real Operations

The moment a factory begins running, three elements enter the system: time, variability, and interaction. These elements fundamentally change how a layout performs.

Time is the first factor.

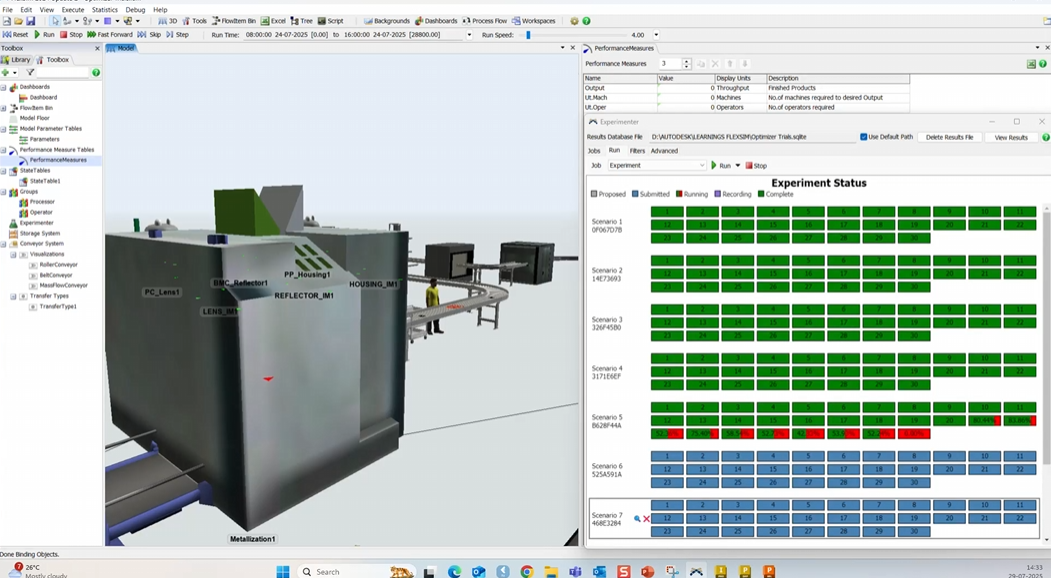

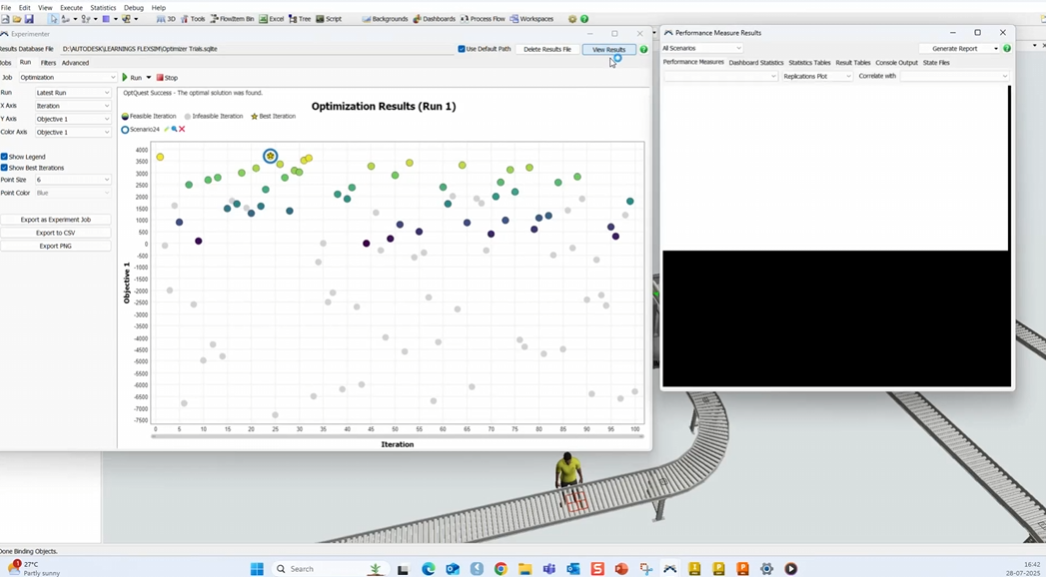

In a real factory, machines have cycle times, changeovers occur, maintenance interrupts flow, and breakdowns happen unexpectedly. Even small variations in processing time can create ripple effects across the line. A machine running slightly slower than planned can cause upstream queues and downstream starvation.

CAD layouts have no concept of time.

They cannot show how production behaves across minutes, hours, or shifts. As a result, they cannot predict throughput or bottlenecks.

Variability is the second factor.

Real-world production is never perfectly consistent. Operator speeds differ. Material deliveries can be delayed. Quality checks may require rework. Absenteeism and shift changes influence productivity. These variations exist in every factory, regardless of industry.

Yet CAD assumes perfect consistency.

It assumes machines and people perform exactly as planned, every cycle, every shift. This assumption rarely holds true once production begins.

The third and most complex factor is interaction.

Once machines, operators, and material handling systems begin interacting, flow dynamics emerge. Queues start forming before bottlenecks. Blocking occurs when downstream buffers fill up. Starvation happens when upstream supply slows down. Forklifts and operators compete for shared aisle space.

These interactions define actual factory performance.

But none of them are visible in a static drawing.

.jpg)

.png)